A Sermon for Good Friday

It’s not fair.

We have plans for the present and the future. We know how life is supposed to go and then, in the blink of an eye, it all gets taken away – death arrives, ready or not, and it simply isn’t fair. Sometimes it doesn’t go that way. When you work in a hospital you have the unique privilege and opportunity to walk through life’s final steps with families. A “good” death, if you can even wrap your mind around that phrase, is one when the family has an opportunity to say goodbye, they know and have accepted what is happening, they are all gathered together, and their loved one slips away peacefully. Unfortunately, a “good” death is not often what we see. Usually, death just happens. It’s not fair. We don’t plan for it, it sneaks up, and it disrupts the life we were planning for ourselves.

Jesus’ death was far from this notion of a “good” death. His death was not fair. He was tortured and brutalized for crimes he did not commit. But for which he went willingly, obediently, to the cross. His death was, however, preceded by many of the markers we see in some of those hospice-type death experiences. The night before he died, Jesus gathered his friends together for a meal. He washed their feet and gave them ways to remember him. Jesus instituted the Last Supper in a ceremony of leave taking: he was saying ‘good bye.’ However, despite the many verses of warning and foreshadowing we read in our scripture, Jesus’ family and friends are taken by surprise when Judas arrives with his kiss and waiting soldiers. Denial plays a large role in the story we walk this week.

Good Friday is the horrible day when reality dawns. Peter has denied Jesus three times, the disciples have scattered, and Jesus is left to face Pilot – and ultimately his own death. The people he came to save scream vile, hateful things at him as he drags his own implement of torture up the hill to the spot where his life will end.

It’s not fair.

In Kate Braestrup’s autobiography, “Here if You Need Me,” she details her experiences as a chaplain for the Maine Warden’s Service – serving almost exclusively in search and rescue missions in the Maine woods. She introduces the tale by sharing the moment in her life when everything changed. Rev. Braestup’s husband, Drew, was a Maine State Trooper. Early one morning, shortly after leaving the house for work and just a few miles from home, his cruiser was broadsided by a box truck, killing him instantly. Braestrup recalls with poignancy the ordinariness of the day when she received the call that forever changed her life: his white cereal bowl, half full with milk was still in their stainless steel kitchen sink, the covers on their bed were still twisted, and you could see the outline of where he lay the night before.

Braestrup writes that “love begins with a body.” Whether romantic or otherwise, we encounter people physically and it is our senses that first form opinions and feelings towards another. Hearing someone’s voice for the first time – seeing the light in their eyes – or the quirkiness of their smile… those are the things that draw us in. Death, like love, begins as a clinically physical thing. The heart stops, the organs shut down, and the cells begin to deteriorate. But in instances of both love and death, the physical nature is overshadowed by the emotion and soul connection shared with the individual housed in the physical body before us.

Having read extensively about what a body goes through after death, Braestrup instructed the funeral director that she wanted no embalming to take place – no makeup to be put on, she would wash and dress her husband’s lifeless body herself, and she would be the one to close the casket for the final time. She also asked to witness his cremation. The physical accompaniment of her husband’s body would be her final act of physical love for him and she would not walk away, no matter how painful. After all, “Drew would do this for me” she thought. She describes the act of gently washing his cold form with a soft cloth, of straightening his State Police dress uniform, and of leaving the room where his empty body lay for the final time. “I am his remains,” she thought.

It’s not fair.

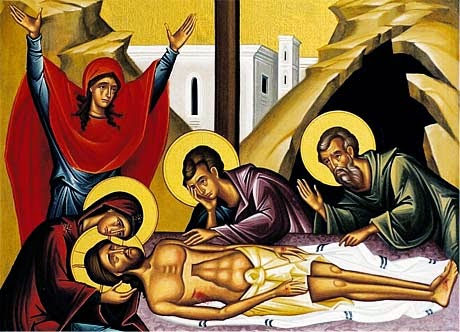

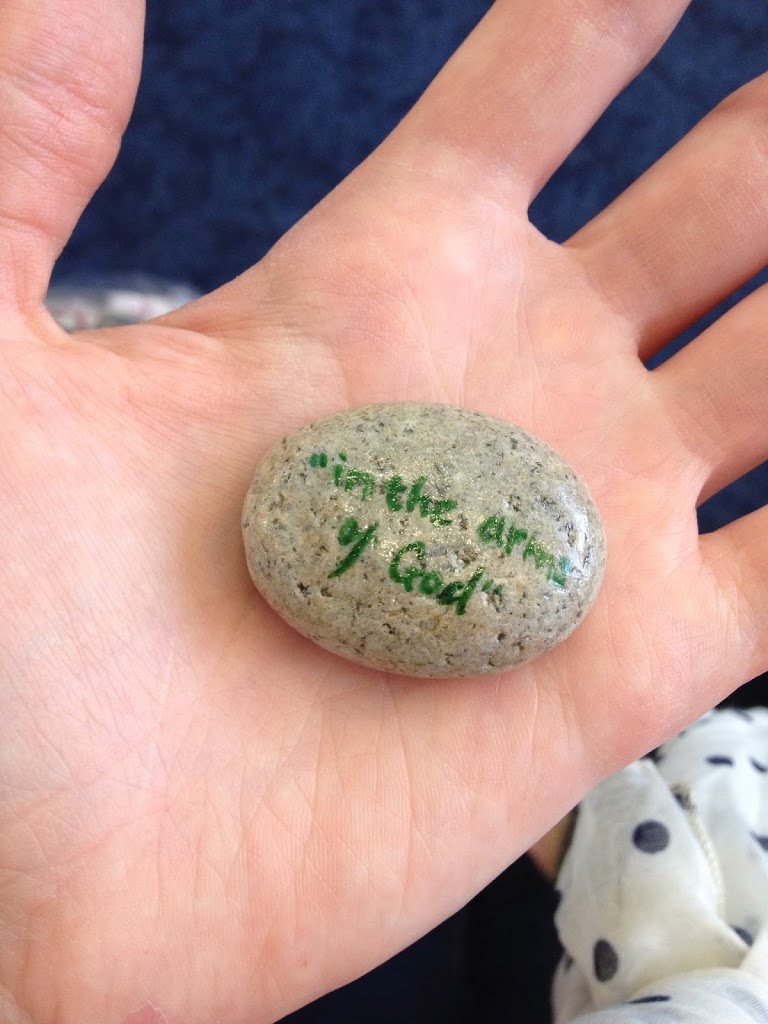

Tonight we wait with John, the beloved disciple, Mary the mother of Jesus and the other Marys at the foot of the cross. We watch, in agony, as the body we love is tortured and as the curtain of heaven is torn in two as the soul of our beloved is released back into the embrace of God. It isn’t fair, but that is what makes is so painfully beautiful. Innocent though he was, Jesus drank from the cup he was given. He sacrificed himself on the cross and he did it for us. So tonight we wait and we cry. We breathe and we despair. We take his lifeless body down from the cross and gently clean it and lay it in the tomb. It isn’t fair, but it is our present reality. We are his remains and how we walk forward from this place is a physical statement about the love we shared.

I was reading an article today and I started to cry. Not ugly sobbing, just gentle tears. As I stopped to ask myself where it was coming from I realized quickly how much the article resonates with where I currently am. I am just “so busy.”

I was reading an article today and I started to cry. Not ugly sobbing, just gentle tears. As I stopped to ask myself where it was coming from I realized quickly how much the article resonates with where I currently am. I am just “so busy.”

… Oftentimes, the most difficult thing we are called to do as Christians is to respond in love. When we are met with anger, we are asked to respond in love. Greif? Respond in love. Hatred? Respond in love. What if I just want to be human sometimes? What if I want to respond with anger, sadness, frustration, or indifference? What then?

… Oftentimes, the most difficult thing we are called to do as Christians is to respond in love. When we are met with anger, we are asked to respond in love. Greif? Respond in love. Hatred? Respond in love. What if I just want to be human sometimes? What if I want to respond with anger, sadness, frustration, or indifference? What then? my parish – that really applies to my Facebook family as well:

my parish – that really applies to my Facebook family as well:

s “baptized” today. The other patients laughed as I insisted we treat him. Our patients inside of the “clinic” space shuddered as he passed. But our doctors embraced the man and listed to his rambling to make sense of what ailed him. After his check-up he was brought to me for prayer. Immediately, he dropped to his knees, shed his baggage and bowed his head. I laid my hands on his head and prayed that God might fill him and heal him. But he is already full of Christ. He knows and loves the Lord more than I could ever hope to know Christ.

s “baptized” today. The other patients laughed as I insisted we treat him. Our patients inside of the “clinic” space shuddered as he passed. But our doctors embraced the man and listed to his rambling to make sense of what ailed him. After his check-up he was brought to me for prayer. Immediately, he dropped to his knees, shed his baggage and bowed his head. I laid my hands on his head and prayed that God might fill him and heal him. But he is already full of Christ. He knows and loves the Lord more than I could ever hope to know Christ.

Recent Comments