Sermon for Easter 2

John 20:19-31

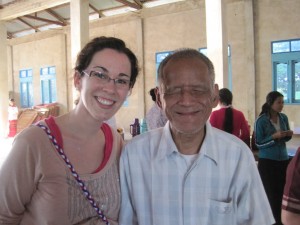

Two years ago I had the opportunity to travel to Myanmar, the country formerly known as Burma, and to meet with groups of Burmese Anglicans while we were there. I traveled with classmates from the seminary and we taught bible studies, met with seminarians, and learned from these silenced people what their lives were like living under military rule as a religious minority.

During our month of travel we met a man named Philip. Philip spoke perfect English and had a knack for writing poetry and cracking jokes. Our group leader encouraged me to talk more with Philip, because – she said – “we had a lot in common.” Wondering what I had in common with this 60-something year old man from Myanmar I sat down and entered a conversation with curiosity. Philip told me that when he was very young the government wanted to institutionalize him, but his mother would not let them.

She knew he was smart, even if they hadn’t found a way to access his intelligence yet. His mother experimented with different teaching strategies until she found one that worked. Eventually she was able to teach Philip to read and to write. When he was about 13 years old a missionary from the United States asked to take Philip to the US for schooling so he could reach his full potential. Reluctantly, his mother agreed, not knowing if she would ever see her son again. It was then that Philip boarded an airplane and traveled to Massachusetts for education.

Philip’s mother was displaying blind faith — the kind blind faith that Jesus rebukes Thomas for not displaying. At least – that is what it sounded like when I first heard the story. This woman handed her child over to a near stranger to take him to a foreign land with the hope for a better life. How many of us could do the same thing? But, then again, how many of us are living under oppressive rule with no hope to get out? The more I have considered Philip’s story the more I realize that while some of Philip’s mother’s trust was blind – much of it was informed by the reality she was experiencing. Some of it was an incredible – unthinkable, really – extension of faith in another person… but that extension of faith was calculated in some ways.

Philip’s mother was displaying blind faith — the kind blind faith that Jesus rebukes Thomas for not displaying. At least – that is what it sounded like when I first heard the story. This woman handed her child over to a near stranger to take him to a foreign land with the hope for a better life. How many of us could do the same thing? But, then again, how many of us are living under oppressive rule with no hope to get out? The more I have considered Philip’s story the more I realize that while some of Philip’s mother’s trust was blind – much of it was informed by the reality she was experiencing. Some of it was an incredible – unthinkable, really – extension of faith in another person… but that extension of faith was calculated in some ways. Then again, who among us hasn’t been Thomas at one point or another? Sometimes we need to have tactile evidence of that which we are asked to understand or believe in order to fully wrap our minds around it. In this post-modern world we require almost scientific levels of evidence for so many things before we are willing to dive in. What do the studies say is the best teaching strategy so that I will know based on little Timmy’s preschool attendance whether he will get into Harvard? Is this treatment for my medical condition the best one? Our faith in God cannot be measured by the same human standards, but we still try.

The question I’ve most often been asked or challenged on when teaching a confirmation class is when it comes to the creed. When asking confirmands where they have the most difficulty in their discernment it most often comes down to the question of the Nicene Creed.

If I asked you all, right now, to close your eyes and then raise your hand if you believe with absolutely no reservation nor any doubt at all that the entire content of the Nicene Creed to be completely true and accurate – how many of us could do that? How many of us “faithful Christians” sitting here this beautiful first Sunday after Easter (congratulations, by the way, for being here on the first Sunday after Easter – that takes hootzpah) can say that we have no doubts at all with regards to our faith in Christ? A handful, at most, I’d bet you. Having faith doesn’t negate the presence of doubt.

Anne Lamott wrote in her book, Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith: “Doubt is not the opposite of faith, certainty is.” The moment we claim to be absolutely certain, without exploration or question, of our faith we are denying the real questions that live in our hearts. When Jesus says, “Blessed are you who have not seen yet still believe” he is encouraging Thomas, and all of us, to trust in all of the evidence that is already around us. We are constantly surrounded by empirical evidence for our faith in the created world in which we live, in the encounters with humans created in God’s image who hold a mirror up in our own lives sharing the light within their hearts, with the feelings and emotions and tugging of the Holy Spirit that we sense each day. But those things do not prove to be enough for Thomas.

Philip arrived in Boston and was enrolled in the Perkins School for the Blind. Philip completed the equivalent of his high school studies in 2 years and so his missionary benefactor helped him apply to Boston University, where he completed his BS in education to become a teacher – again in only 2 years. Since he still had a year left on his student visa, Philip then got a job at a piano tuning shop in Somerville and he learned the trade of piano tuning. After five years in Massachusetts Philip returned to Myanmar, despite being offered asylum in the US, to share the knowledge he had obtained in his time away. I was enthralled by Philip’s story. I asked him, what the hardest part of growing up blind was for him and he said, “I can’t think of a hardest part of being blind. A hardest part of life, yes; but of being blind… it is all I know. Sighted people always assume the darkness must trouble me but I don’t think I have experienced darkness. I know what colors and light must look like because my friends have taken such care to explain those things to me; but darkness has been described as the ‘absence of colors and light’ and I cannot fathom what that would be like because, by the grace of God, my whole life has been filled with color and light.”

Philip arrived in Boston and was enrolled in the Perkins School for the Blind. Philip completed the equivalent of his high school studies in 2 years and so his missionary benefactor helped him apply to Boston University, where he completed his BS in education to become a teacher – again in only 2 years. Since he still had a year left on his student visa, Philip then got a job at a piano tuning shop in Somerville and he learned the trade of piano tuning. After five years in Massachusetts Philip returned to Myanmar, despite being offered asylum in the US, to share the knowledge he had obtained in his time away. I was enthralled by Philip’s story. I asked him, what the hardest part of growing up blind was for him and he said, “I can’t think of a hardest part of being blind. A hardest part of life, yes; but of being blind… it is all I know. Sighted people always assume the darkness must trouble me but I don’t think I have experienced darkness. I know what colors and light must look like because my friends have taken such care to explain those things to me; but darkness has been described as the ‘absence of colors and light’ and I cannot fathom what that would be like because, by the grace of God, my whole life has been filled with color and light.”When Jesus says, “blessed are you who have not seen yet still believe” he isn’t calling us into blind faith. Jesus is calling us into the faith of our ancestors. He is calling us into faith in the God who created all things, who sent manna into the wilderness, who led us out of exile, who came to earth to walk amongst us and then died on a cross and rose again for love of us. Jesus isn’t calling us to blind faith because blind faith doesn’t exist – just as darkness doesn’t exist to a blind man. Our God is a God who has been palpably present since the beginning of time; Jesus is calling us to trust all of our senses as we seek to encounter the divine dwelling among us.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.